Unless you’re an Olympics historian or a high jump aficionado, you’ve probably never heard of Dick Fosbury. I certainly hadn’t, until a few days ago when I chanced upon the interesting story of a teenage, American high jumper who struggled to scale the required height needed to qualify for his high school track meets. A common technique at the time, known as the straddle method, required athletes to adopt a position where they had their faces and bodies looking down on the bar as they lifted their legs individually over it. This was the first technique that Richard Douglas “Dick” Fosbury was taught, but having struggled to coordinate the complex motions required, he started experimenting with other ways of doing the high jump.

High jumping too, was undergoing its own transformation at the time. The landing surfaces had historically been sandpits or other low and relatively hard surfaces, which required jumpers to land on their feet or at least in some sort of measured position to avoid injury. But these hard surfaces were gradually replaced with softer, and higher foam matting, which reduced the athletes’ chances of injury, and more importantly, resulted in more possibilities regarding their landing positions. The softer, higher surfaces made it possible for athletes to land off their feet with minimal risk of fracture or injury, and in turn, made it possible for them to explore new ways to scale the bar. This removed a key constraint, leaving the only other major constraint, in the form of governing rules, to consider. The key rule here was that athletes had to jump off one foot at takeoff, but there was no rule to specify how they had to go over the bar, or how they had to land, as long as they scaled the bar without knocking it off.

Enter Dick Fosbury, at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City. Before then, there were many popular techniques that athletes used, including the scissors jump, the eastern cut-off, the western roll, and the aforementioned straddle technique, each of which built on and/or replaced the technique that came before it. Fosbury had experimented with a new technique in the years leading up to the Olympics. Instead of approaching the bar head-on and scaling it with his face and body looking down at the bar, his technique involved leaning away from the bar in the run-up to it and scaling it backwards. As one reporter put it, he looked like “a fish flopping in a boat”.

The technique and the movement lacked the perceived grace and optics expected at the highest levels of competition. But crucially, it allowed Fosbury to lean into his intuition and experiment with techniques that enabled him to scale record heights and win the gold medal. His “flop” might have looked odd at first, or even a bit silly. The pundits certainly didn’t hold back in making their feelings known. But it didn’t matter. Fosbury had a goal in mind, worked within the rules and constraints, and adapted his technique accordingly. And it worked for him.

What was once derided as a flopping fish technique has since become the dominant technique in high jumping, having gained popularity since the 1968 Olympics and enabled generations of athletes to break and set record after record. Fosbury was once labelled the “World’s Laziest High Jumper”, but his name is now associated with the most successful high jumping technique to date. Unless you’ve seen black-and-white footage of Olympic high jumps, chances are you’ve never seen any other technique apart from the Fosbury Flop performed at the prestigious games.

If we leave this story here, then we might be falling prey to the survivorship bias. We couldn’t possibly draw conclusions from one tiny aspect of one of the countless accounts that exist in the universe. For instance, there’s no telling how many other athletes experimented with unconventional techniques and failed, in high jumping and other sports. Trying out something new and different may not always pan out the way we hope. In fact, more often than not, it’ll result in failure. But even that failure will be instructive and beneficial, in the sense that it offers data points we can learn from. This is all to say that what we can draw from this account is a framework for experimenting, the intuition to go against the grain, the creativity to leverage constraints, and the courage to look silly.

All these are crucial in the creative landscape we find ourselves in today. In a world that eschews failure and celebrates success, in a culture that marginalises the unconventional and venerates the mainstream, in a landscape that incentivises conformity and penalises experimentation, there’s no better time to embrace the unconventional and adopt the mindset of continuous experimentation. Tried and tested measures exist for a reason, to keep us safe and give us a measure of certainty and familiarity in a world full of uncertainty. Familiarity is all well and good, but it can only get you so far, up to a point. To go beyond that point, sometimes, a flop is just what you need.

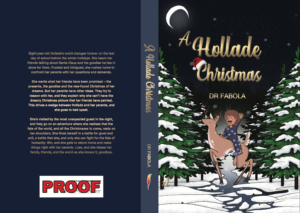

P.S: My new book, A Hollade Christmas is out everywhere now. You can get it in all good bookstores and from all major online vendors.